CWL 395:

persons and things

Since the time of the ancient Greeks, one of the most fundamental distinctions in Western thinking has been the distinction between persons and things. Although we have extended personhood to previously "thingy" categories (slaves, women, children), we have always been, and continue to be, troubled by what lies between these two cateogies. Is a fetus a person, or a thing? A blastocyst? A gorilla? A dog? A beetle? A bacterium? A person is obviously a person—but is a person always a person? What about a person on life support? A person born without a brain?

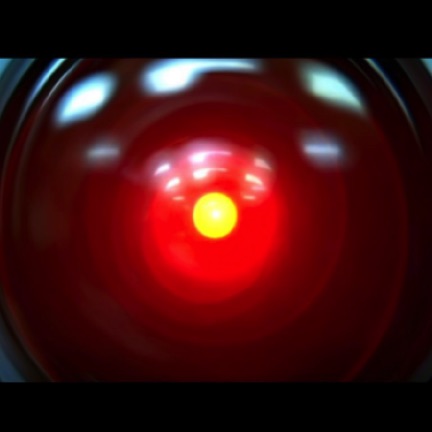

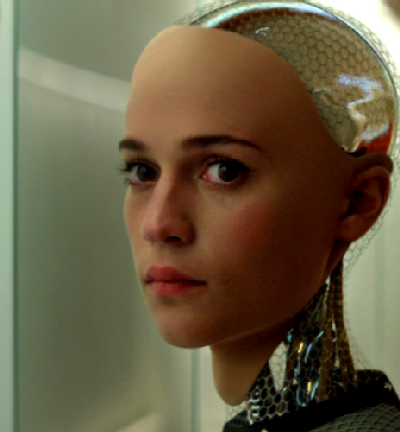

In this class, we will look at something else between personhood and thingness: the artificial person. How does artificial life challenge our concept of the person / thing division? The notion of creating an artificial person is hardly new—as we'll see, since the ancient Greeks, we have imagined the possibility of artificial persons. Beginning in the 19th century and the rise of modern medicine and chemistry, we began to understand that perhaps we were also something mechanical, reproducible. We'll look at the history of representations of artificial persons from Greek mythology to contemporary television, as well as some of the philosophy behind artificial intelligence and artificial life (Turing, Dennet, Searle, Haraway, etc.). Texts range from children's movies and books (Pinocchio, The Wizard of Oz) to ballet (Coppelia), from silent film (Die Puppe or The Doll) modern movies (Ex machina), and from the Czech play (R.U.R.) that gave us the word "robot" to contemporary Swedish television (Äkta människor or Real Humans). We will find a consistent set of fantasies about the artificial person, who almost invariably falls into one of four categories: the obedient worker, the perfect woman, the real boy and the unjust enemy.